Voxelizing the Human Brain

How We Created the First Map of Brain Mitochondria

BEHIND THE PAPER

Full-Text Link to Primary Source

“Time will tell if that’s correct, and if there is a deeper reality through which mitochondria help the unfolding of human consciousness to be experienced.”

This is the story of how we produced the first brain map of mitochondria—or the human brain bioenergetic landscape. The paper was published in the journal Nature in March 2025. It was also covered in a Nature Neuroscience Research Highlights and in a News piece by Nora Bradford in Nature Magazine.

A Moment of Inspiration

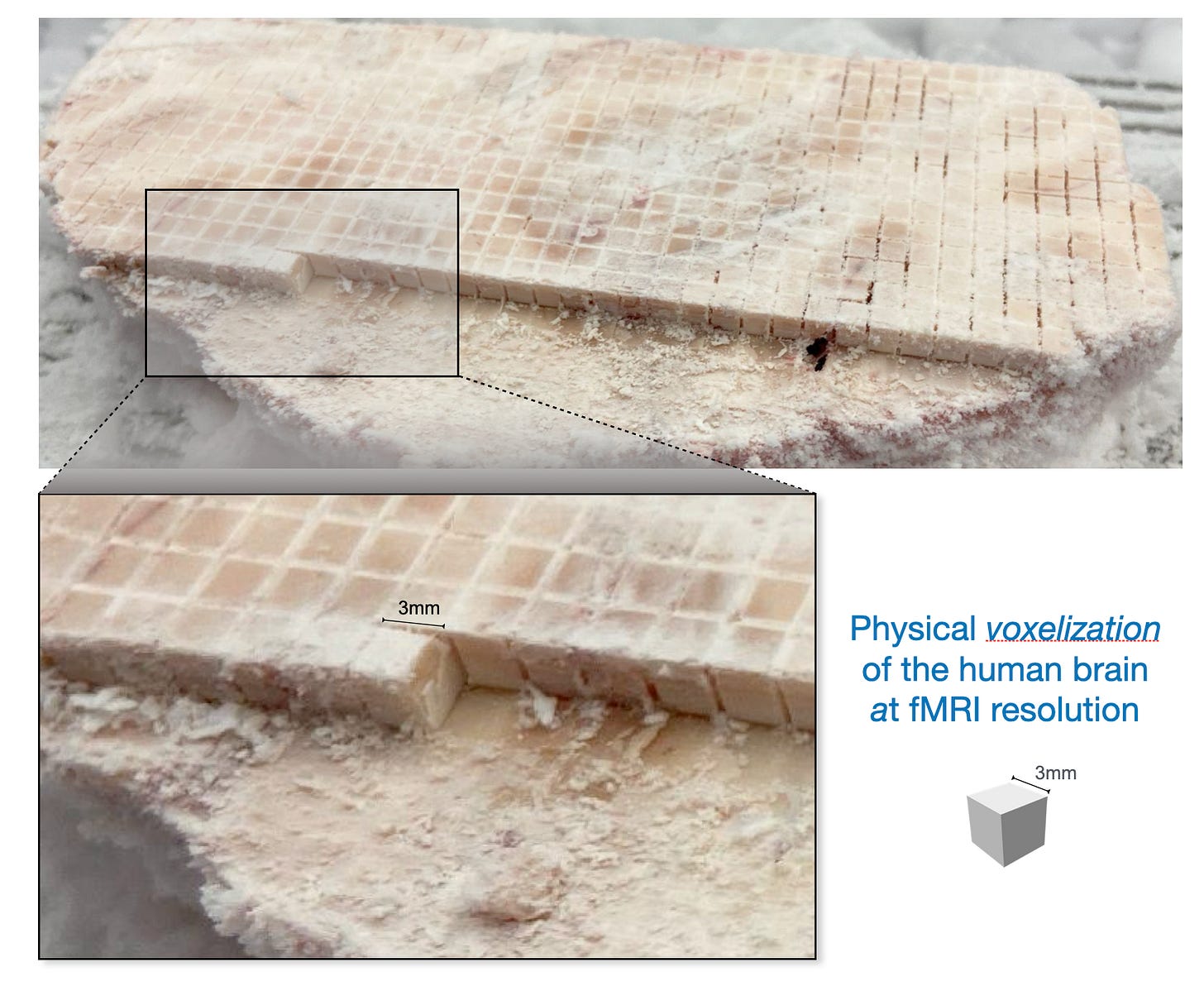

The journey started with something like this: “What if we could cut the brain into tiny little cubes, the same size as neuroimaging—3 by 3 by 3 mm, but in real life—little cubes of brain?” I asked my colleague Eugene Mosharov, who shares the office next to mine in the Kolb Research Building at Columbia. “If we can cut the brain into little cubes, we can profile the mitochondria in each one and reconstruct the whole brain mitochondrial map. This would be MitoBrainMap version 1.0.”

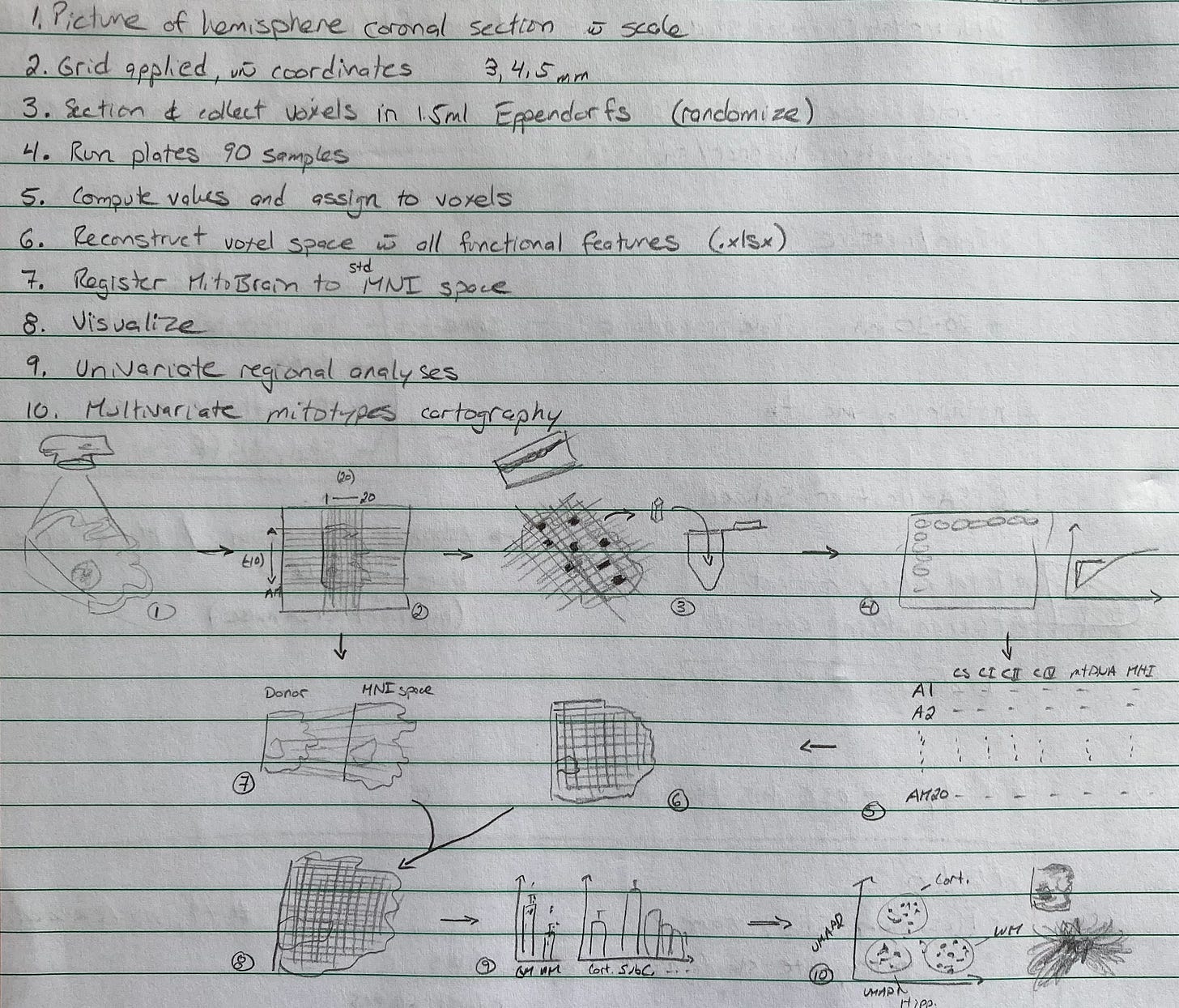

Here is what my lab notebook entry from November 2020 looked like:

And we did just that.

The Power of Collaboration

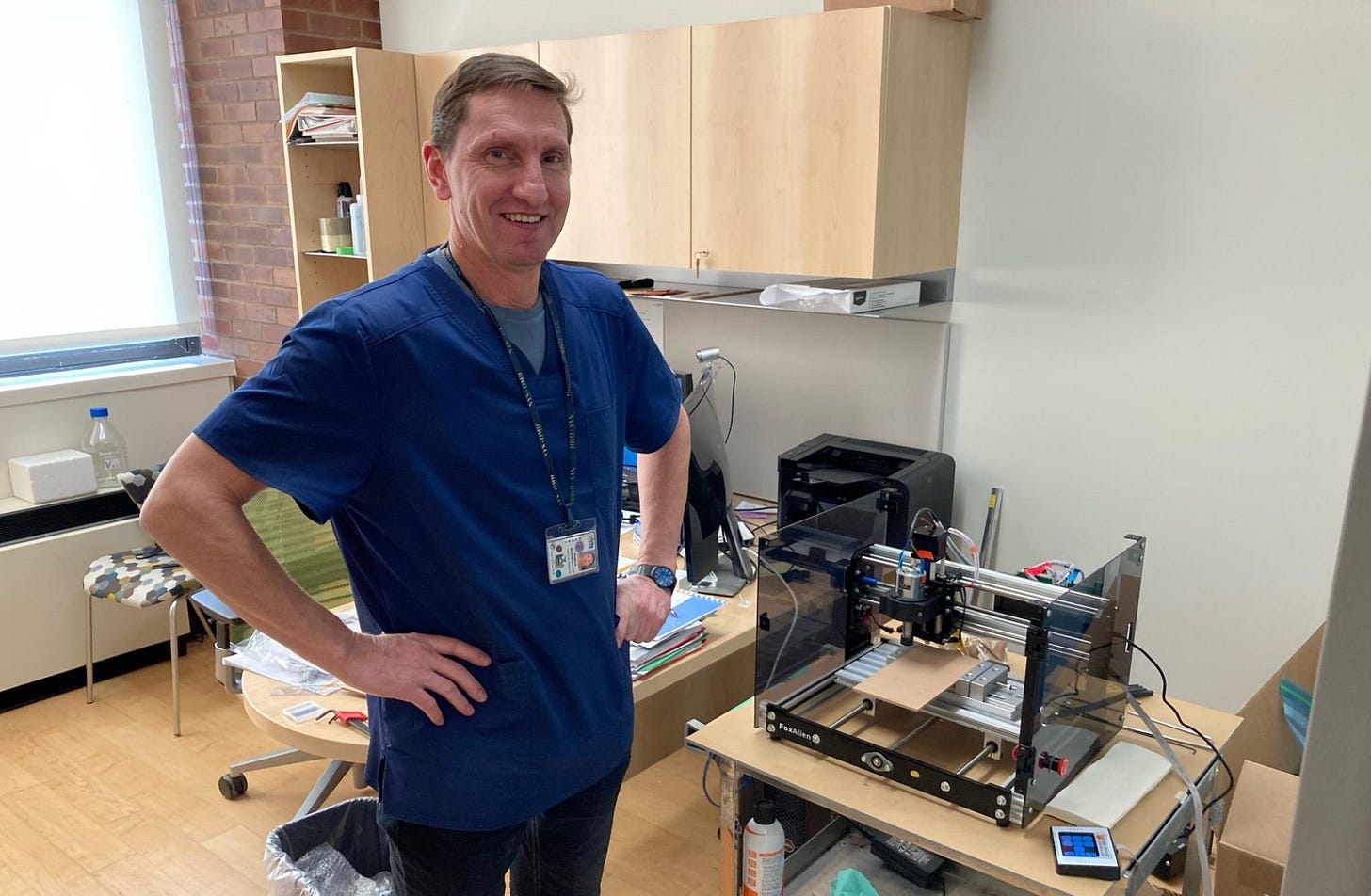

Eugene trained as a chemist in Russia. Hardied by minimal resources and the need to rig everything in graduate school, he quickly learned to think and work like an engineer. He rigs, repairs, and builds all sorts of things. And fortune had it that he worked for most of this career in a neuroscience lab, dealing with mouse brains and neurons.

So, when I first pitched the idea of designing something that could turn a human brain into cubes, I knew Eugene was the guy to make this happen!

It took only a few conversations to peel the Russian skepticism off of Eugene and get him excited about the project. “But where do you find a brain?” he asked.

Our colleagues at the New York State Psychiatric Institute had been, I had recently learned, storing precious brains in their brain bank freezers for a few decades. Surely they had a few good brains we could use?

“How many brains do you need?” asked Gorazd Rosoklija at the brain bank. He was visibly intrigued by our ambitious project, but communicated with a certain tone mixing gravity and annoyance to ensure we knew how precious a resource this was.

It was an awesome project; everyone could feel it. So Gorazd and his colleagues said yes, and helped us find the best brain for the task.

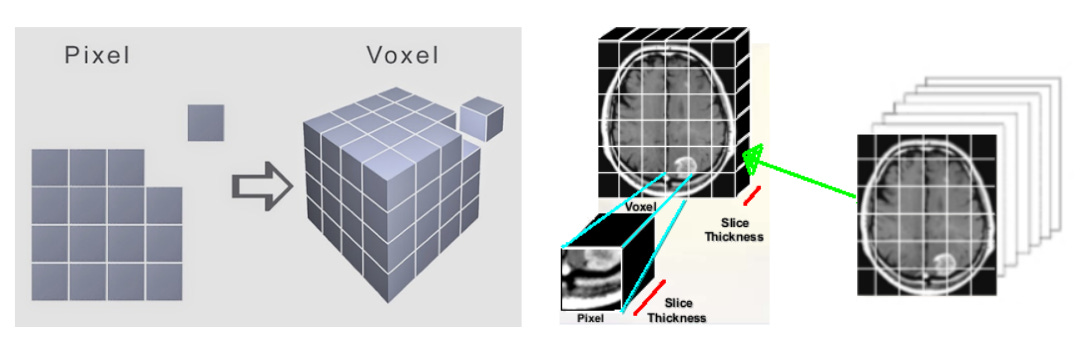

The problem was that, after some calculations by our collaborator Michel Thiebaut de Schotten, we determined that a brain would contain >100,000 voxels. “Voxels,” a combination of the words “volume” and “pixels”, are cube-shaped units of space. In our case, 3x3x3 mm cubes.

The largest project we had done yet was 571 samples in this paper. We could get to a thousand, but not more. This ended up being perfect, because the brains were stored as slices, rather than whole brains. And we estimated that each slice could be cut into about 600-1,000 cubes.

After about 6 months of fiddling, discussions, optimization, and programming, Eugene walked into my office with the confidence of a child who solved a hard puzzle for the first time. “Do you have a moment? You want to see this?”

After weeks of breaking drill bits and perfecting his program to engrave a precise 3x3x3mm grid of little cubes in various materials, Eugene had done it. He had developed a program to gradually etch horizontal lines, then vertical lines, progressively getting deeper and deeper, until the whole surface of the brain was effectively turned into cubes.

We had tiny brain cubes, called “voxels”, at neuroimaging resolution!

Preparing the Brain and Building the Team

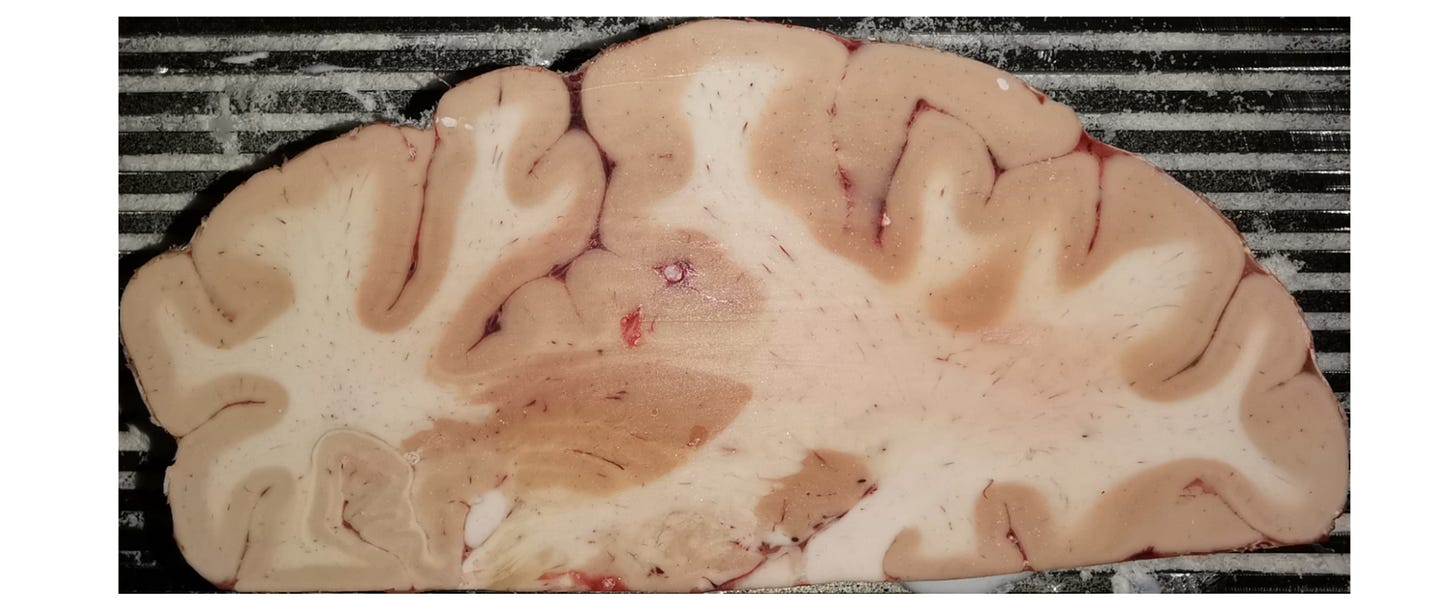

One day, I walked down to see how Eugene was doing. He was working on the brain slice. We had retrieved it from Goradz’s freezer together, so I had seen how big it was. But now Eugene had applied his “cleaning” algorithm, which removed the thin layer of frostbite inflicted by years in the -80C freezer.

This was my first encounter with the full beauty of the human brain. The cortical grey matter that surrounds the whole thing, its smooth involutions and convolutions thought for so long to be the seat of higher rational thoughts. The deep subcortical (under the cortex) clusters of neuron cell bodies, called nuclei, like the putamen and hippocampus, which are associated with reward and memory. And the impressive white of the white matter. Myelinated axonal highways that connect front to back, left to right, and every part of the brain to some other part.

Masterfully organized, a structure of immensely beautiful complexity that is difficult to depict in words. “Wow, this is so beautiful,” I whispered to Eugene. That day, I went from understanding neuroscientists’ interest in the brain, to truly loving the brain.

While this was happening, Ayelet Rosenberg, the talented student in my laboratory who had produced what was then the largest mitochondrial health index dataset in mouse brains, had been developing a strategy to individually harvest the brain voxels, delicately transfer them into pre-weighed tubes to obtain their precise weight, and process them with our mitochondrial platform. But this was more than a one-person job. To help Ayelet with the monumental task of harvesting, weighing, and processing hundreds of cubes all at once, we recruited another student, Snehal Bindra.

Snehal, a native of New Dheli, India, and now a UCLA student, showed up at my door one day. That was a week after I ignored an email she sent me. She was there, looking very proud and confident, with a good dose of humility: “Hi, Dr. Picard. I’m Snehal. I saw your work on the mind and mitochondria. I need to work for you and your lab.” Plain and simple.

Snehal joined the lab for the summer. She worked on an ovarian cancer project where we profiled mitochondrial phenotypes in relation to psychosocial factors. Before Ayelet, she held the previous record of 358 samples.

In 2021, our two record holders joined forces for the heroic effort to collect, without mistake, the human MitoBrainMap v1.0 voxels.

Bearing the Cold for the Sake of Science

One added challenge here that Eugene seemed quite fit for was that the human brain section was large, and the physical voxelization needed to be done when the brain was frozen. If we thawed the brain section, it would collapse like a piece of melting jello. There would be no way to cut it and collect voxels. It would be mush. So, the whole thing—the brain section, the drilling computer numerical control (CNC) robot, and the computer controlling the robot—all needed to be in the cold -20C freezer room in the basement.

Eugene too, it turns out, had to be in the cold to make sure everything was running smoothly. He wore a thick winter jacket, big mittens, and a heavy tuque (knitted hat). It reminded him of the cold Russian winters, I think.

He always felt that for something to be worth it, you needed to suffer a bit. That day, with the precious brain section in place, the robot ran for 4.5 hours.

Video by Eugene Mosharov

“How many voxels?” I asked, excited when I saw Eugene coming back from the cold room.

Eugene said calmly, “703,” with a glorious expression of pride showing his accomplishment on his face. “But we are not done yet,” he said, reminding me that most of the job still had to be done. He was done but knew that the road ahead was long.

Eugene had done it, this time on the “real brain”—he had physically voxelized an entire coronal section of the brain from a healthy human donor. The brain was from a 54-year-old man with no physical or mental health issues, who died suddenly of a heart attack. Within 8 hours of his death, his brain had been removed, cut and frozen—a fairly short amount of time—ensuring that the biology of his brain mitochondria would be preserved to teach the world about the brain bioenergetic landscape.

We were so grateful.

Scaling Up

The next day, Ayelet and Snehal were done harvesting and weighing all of the cubes. We met quickly to discuss their plan.

“How do you feel?” I asked. “Good, it worked!” Ayelet said. The voxels weighed on average 27 mg, as expected from the known density of water (remember we are mostly water) and the 3x3x3 cube sizes.

“Ha, beautiful!” I congratulated them. They were both excited and had a plan for the next 3 weeks. In total, they ran 19,668 assays on the 703 voxels to create the first MitoBrainMap.

But to make this map useful, we had to face a challenge of scale. While cell biologists usually study things at the scale of the cell, and mitochondrial biologists are usually content with staying within the confines of the cell, cognitive neuroscientists operate at the scale of the whole brain. To do so, they use neuroimaging that can capture brain structures and some aspects of brain activity at the whole brain level, over time.

Over the last two decades, we have learned that it’s by measuring distributed activity patterns—energy patterns, as it were—across the brain, the most meaningful correlates to human experiences can be made. So how can we bridge the scale of mitochondria in single voxels with the scale of the whole brain?

This is when Michel Thiebaut de Schotten really brought this project to another level. Michel is a neuroanatomist in Bordeaux, France. He performed dozens of human brain dissections, touching and feeling different parts of the brain directly, following white matter connections that unify the whole thing into a working organ. Michel was originally trained as a neuropsychologist, but he later espoused the wonders of neuroimaging.

He developed, with the speed of a genius, programming competency allowing him to navigate the complex multi-dimensional space of brain signals, and to extract meaningful information that can be related to human behavior.

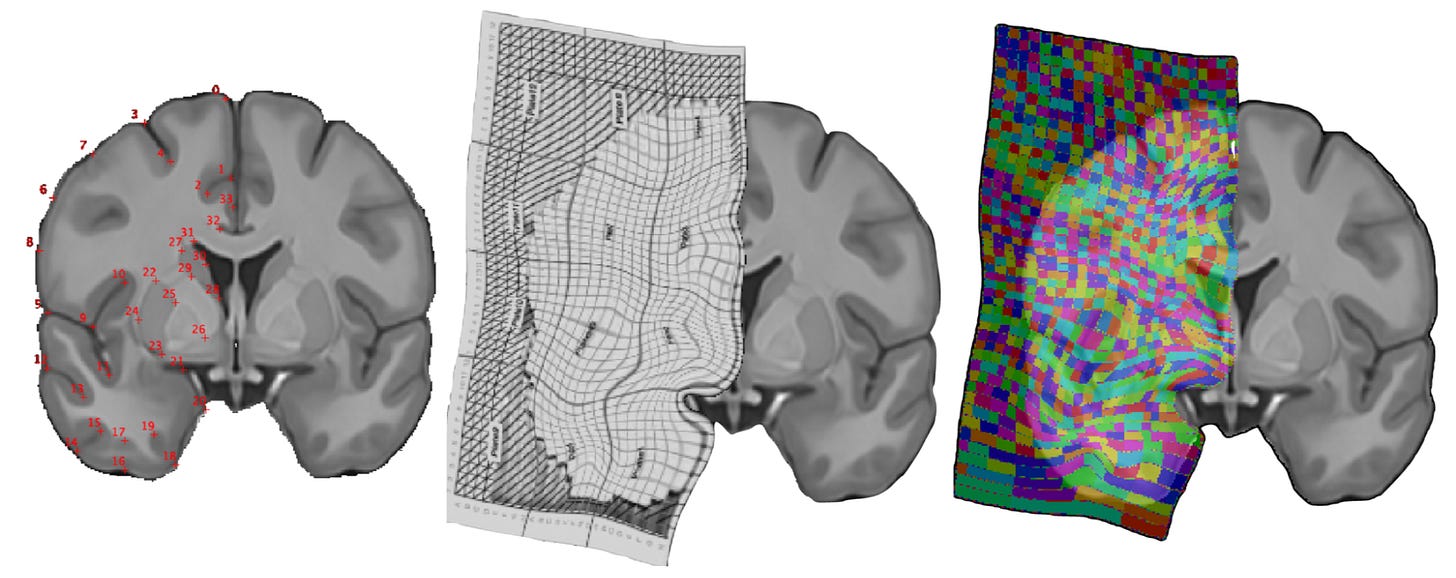

“Michel, can we register the MitoBrainMap v1.0 to the standard MNI space?” I asked.

The Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space is the accepted “human average” of the brain that many neuroscientists use to compare, integrate, and analyze their data. I suspected that bringing our MitoBrainMap into this standard space was key to making it useful. “Ouais (yes), of course,” said Michel on Zoom in his lovely, pronounced French accent. “It’s going to take me a few hours to find which part of the brain we are in and align cortical and subcortical landmarks point-by-point,” he explained with a mix of enthusiasm and dread.

“I’m gonna do it manually so we know it’s well done.” And with confidence and hope that something good would come out of this effort, off he went.

Creating and Sharing Our Map of the Brain’s Energetic Landscape

A few weeks later, Eugene and I opened our inboxes to find Michel’s impressive image of the transformation, or rather deformation, applied to our 54-year-old male brain to fit the average MNI human brain.

We could now look at our mitochondrial activities in the same standard reference space that all neuroimaging scientists worldwide use for their neuroimaging data.

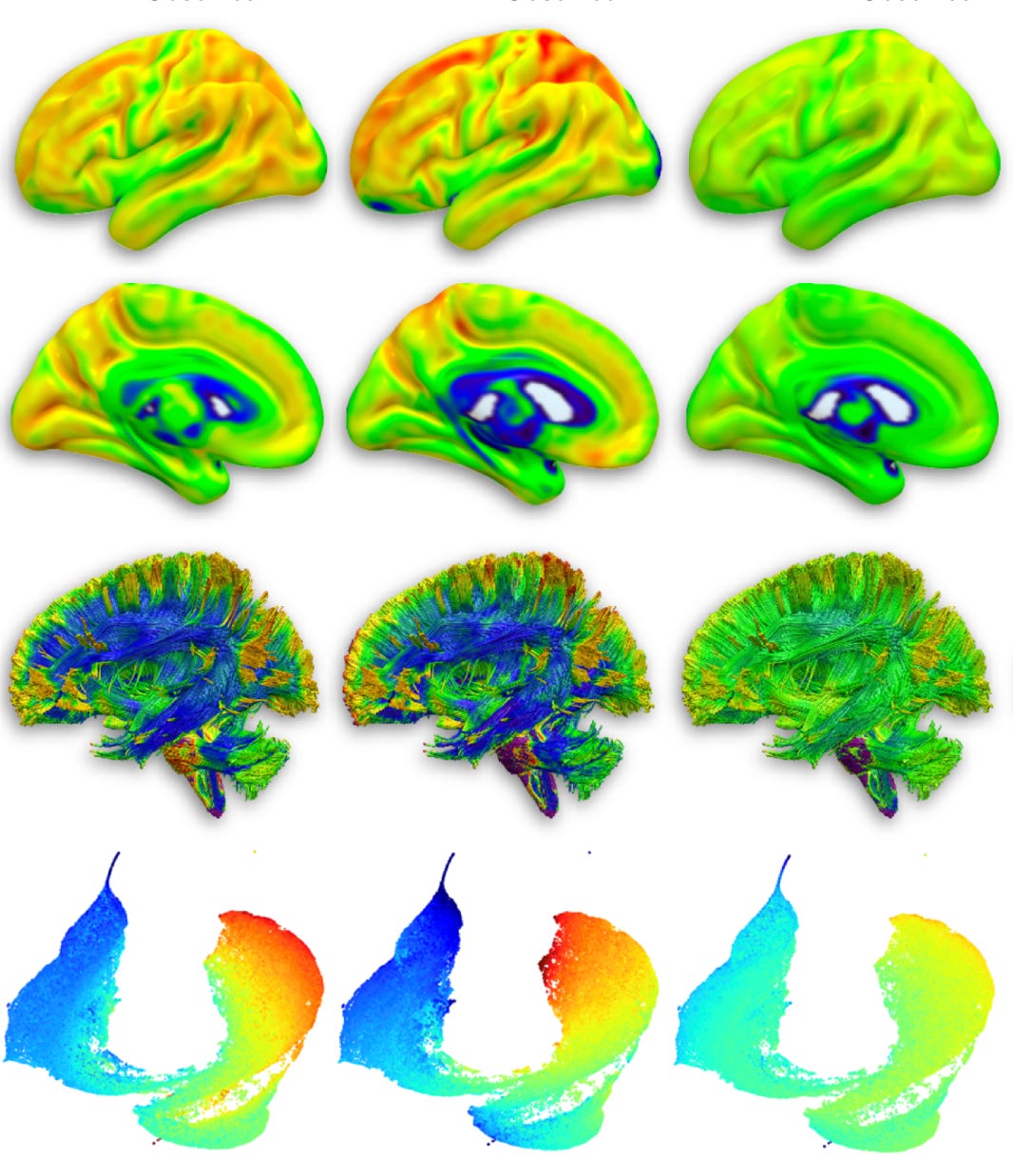

Seeing the opportunity, Michel developed a computational model to predict—using standard neuroimaging data only—mitochondrial content and energy transformation capacity. A few iterations later, he had produced the first probabilistic map of mitochondrial biology across the human brain. He was excited, I was ecstatic, and Eugene was solemnly happy, now eager to write the paper and share this with the world.

So here are the probabilistic maps of mitochondrial features projected onto standard brain space, enabling comparison with neuroimaging data across studies and datasets.

After months of writing, revisions, and responding to reviewer feedback, the paper was finally accepted for publication in the journal Nature just a few days before Christmas in December 2024. Eugene, first author on this paper, was delighted and got a bottle of Champagne for us to share.

This was the first project on the human brain for our Mitochondrial Psychobiology Laboratory. Through this work, we helped in a way to bring the science of mitochondria and energy to the scale of the whole brain, where some suspect human experiences energetically unfold.

Time will tell if that’s correct, and if there is a deeper reality through which mitochondria help the unfolding of human consciousness to be experienced.

We welcome everyone to join us on our journey to establish a new field called Healing Science. If this work resonates with you and you would like to support this kind of research at the intersection of science and experience, please share this Substack with your community.

You can also support the developing Energy and Healing Institute | EHI.

Incredible work bridging cellular bioenergetics with whole-brain imaging. The way this team aligned mitochondiral data to MNI space is kinda genius since it lets any neuroimaging study tap into these metabolic patterns. I remeber struggling with similar cross-scale issues in my own lab work. Linking subcellular machinery to macroscale brain activity could actually reshape how we interpret fMRI energy signals.